Ghana recently held a Family Planning (FP) 2020 stock-taking event as a countdown to the country’s FP 2020 goals and commitment made during the 2012 London summit. The conference, which brought together multi-sector stakeholders, reviewed Ghana’s progress, challenges and options to accelerate achievement of the country’s FP 2020 targets and commitment.

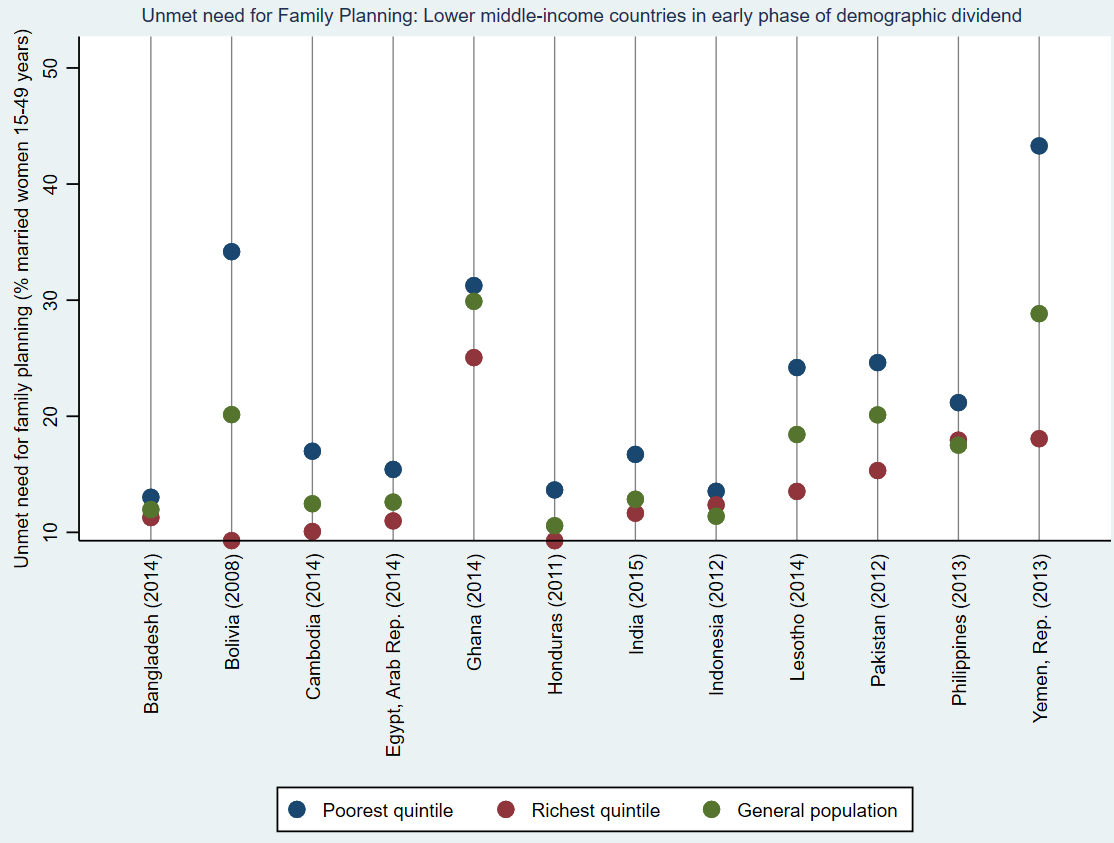

With a high unmet need for family planning compared to many other early demographic dividend countries across lower-middle income countries, three in 10 Ghanaian women who want contraception to space or limit births currently lack access. Access to contraception is a key strategic lever for development – to empower women, improve investments in children, and ultimately contribute to poverty reduction. Unplanned pregnancies, including teenage pregnancy, perpetuated by lack of access to family planning are linked with higher risks of birth complications such as maternal deaths and early child deaths, and malnutrition in children under-five, particularly in the critical window of child development - the first 1000 days. Securing access to family planning services therefore remains a critical component of building human capital in Ghana.

Figure 1: Unmet need for Family Planning across early demographic dividend LMICs (source: Author's analysis of World Bank Health Equity and Financial Protection Indicators database)

In response to this challenge through the FP 2020 commitment, Ghana is taking strides to ensure finance and service availability are not barriers to access FP services. To achieve this, the government has approved a dedicated budget line to finance essential health commodities including contraceptives; and is currently in the process of including access to a wide range of modern contraceptive methods in the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) benefit package. The latter strategy complements a national effort to ensure health financing reforms in the country are oriented toward attainment of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Ghana is not alone in this quest and can learn from efforts of other countries that have towed a similar path.

Lessons from Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region suggest including a broad range of FP methods within a Social Health Insurance (SHI) benefit package remains a viable channel to expand FP access for the poorest; at the same time, intensified UHC reforms should be simultaneously explored to ensure broad coverage of population can benefit. While the NHIS premium is exempted for indigents (i.e. people designated as poor) by the Government of Ghana, overall population coverage is modest at 40% in 2014 and even lower in 2017 at 35% based on administrative data. To ensure optimal results from an expanded NHIS benefit package, it is important to expand NHIS coverage particularly amongst the informal sector and poorest population. In Peru, Honduras and Guatemala, despite the inclusion of FP in health benefit packages, out-of-pocket spending (OOPS) for FP remained a substantial part of total FP expenditure; a similar pattern is noted in Chile and Columbia – both countries with high SHI coverage and comprehensive FP benefit packages. The high OOPS is in part attributed to co-payments, variation in service availability and long wait times with some clients resorting to private purchase of FP services. This implies inclusion of FP in an SHI benefit package isn’t a silver bullet to remove all financial barriers to FP access and will require complementary strategies.

Ghana is taking steps to ensure such complementary strategies are in place to support an expanded NHIS FP benefit package. These complementary strategies include increasing the share of domestic financing of FP commodities from 25% to 33% to be assured through funding from the dedicated health commodities budget line. In addition, pilots are underway to ensure Ghana’s Community-based Health Planning Services (CHPS) can provide a range of modern FP methods to communities around them. In the LAC experience, it was SHI coverage, rather than access to free public services (such as Ghana’s CHPS) that was a bigger factor in improving access and uptake of modern FP methods. Reasons for this varied but centered around low service availability and readiness at points of care for free public health services. As a lesson learned, to ensure that the CHPS strategy fully complements NHIS in increasing modern FP uptake, Ghana should ensure commodities security to the last mile, and availability of well-trained frontline health workers across a variety of modern methods who are also vast in human rights and choice-oriented approach to FP services. Given informal reports of varying FP service charges in government facilities which deviate from the official government subsidized FP service rates, partnership with local media houses and a concerted public information campaign can help increase awareness on FP benefit packages and reduce inappropriate rent-seeking behavior by FP service suppliers.

Financing and achieving Ghana’s FP 2020 goals will avert an estimated 2.3 million unintended pregnancies, 30,000 child deaths, and more than 5,000 maternal deaths between 2016 and 2020. Overall, as more FP needs are met, families are better able to tailor family size to available resources, leading to fewer maternal and child deaths, better nourished and nurtured children, with ripple social and economic effects on individuals, families, and the society at large. As an avid advocate for investments in interventions promoting child development and human capital, Ghana’s reinvigoration towards sustainable financing for FP is a welcome development. Acknowledging Ghana’s ongoing challenge with NHIS’ fiscal sustainability, establishing an evidence-based approach towards a prioritized benefit package is more important now than ever. The World Bank, through ongoing advisory services on Ghana’s UHC reforms and operations support for access to maternal, child health and nutrition services, remains committed to support Ghana’s FP 2020 journey as a strategy to boost the country’s human capital and economic growth.

Author: Ibironke Folashade Oyatoye

email: ioyatoye@worldbank.org